Caspar David Friedrich and German Romanticism

To react with wonder and awe to the created world and then endeavour to communicate something of that feeling to the rest of humanity. If this can be said to be the vocation of the artist, then the work of the great German Romantic, Caspar David Friedrich towers above that of all others. Friedrich was born in Griefswald in northern Germany in 1776 and after a brilliant career, died in obscurity in 1840. Only in relatively modern times has his art been discovered and given due recognition.

His mother died in infancy, two of his sisters died young. He witnessed his brother drowning in an ice skating accident in the Baltic, an event that explains his melancholia and his obsession with death in some of his paintings. He had a deep religious faith, deriving no doubt, from his father’s reading of the Bible.

Influence

German Romantic painting emerged as a reaction against the Enlightenment. In the 18th century there was a belief that all human problems could be solved by the application of pure reason. The Romantics rejected the emphasis on reason put forward by the philosophers, Rousseau and Kant, replacing the rationalist world view with an outlook based on the sensual and emotional. Romantic art now defined a new set of beliefs, and artists allocated prime importance to intuition and the unconscious, the idea of truth to the individual self and one’s inner feelings.

Romanticism was a return to nature, which had become a new kind of religion, because the age of reason had done away with religion. Hand in hand with the return to nature there arose a new passion for landscape painting. Painters began to discover divine and mystical elements in nature and to explore man’s position within it. In addition, the Romantic landscape became the expression of a German yearning for the unification of a fragmented country: the expression of a German dream.

The biggest influence on Friedrich and other German artists of this period were the ideas of the philosopher, Schelling who said: “Lying beneath the surface appearances of nature is a spirituality waiting to be revealed by the painter or poet.” In his technique and general approach to painting, Friedrich followed the German tradition of respect for traditional rules of space and the representation of the human figure.

His Aims

Friedrich looked on landscape painting as a means of celebrating the natural world and the divine power that created it. His landscapes are really religious paintings. “The Divine is everywhere, even in a grain of sand,” he wrote. He wanted to symbolize the realm beyond the senses, that place of serenity and peace which he never tired of seeking. His conclusion was that God is in all things and that the landscape in all its manifestations is a reflection of His presence. God, like Nature, is infinite. Through art, spirit becomes accessible to the physical senses.

Friedrich stressed the solitude of man in front of creation. He sought to depict emotions such as loneliness and desolation. His paintings always drew out the spiritual side of the landscape and often depicted nature at its most melancholic: lonely stretches of sea and mountains, or snowscapes bathed in a strange and eerie luminosity.

The middle distance is often eliminated from his paintings. There is a sharp contrast between the foreground, which is often dark and detailed, and the background which fades out of reach, lost in a fog or luminous haze. For him, the fog represented the cloud of our unknowing.

In classical landscape, everything was visually clarified. In the 18th century, according to certain theorists, fog meant separation from God and aimless wandering. Friedrich wrote: “Landscapes wrapped in fog seem more vast, more sublime, fog stimulates the imagination and reinforces expectation.” This introduces the principle of total uncertainty, an uncertainty as to what lies beyond our senses, or what the future may hold. The foreground is the here and now, representing our imprisonment in this world. The background, often shrouded in fog, symbolizes the infinite, the realm beyond the senses, that place of serenity and peace which he never tired of seeking, but which seems to be inaccessible. The vast gulf between the foreground and background symbolizes our separation from what lies beyond. His paintings featured solitary figures absorbed in the meditation of nature, often placed in lonely settings amidst ruins, mountains and the rocky Baltic coast. In many of his paintings a figure in the foreground stands gazing into the distance, representing the solitude of man still firmly rooted to this world but yearning for the infinite – man as a stranger here. His spiritual intentions were expressed in simplified, rather geometric compositions, often using muted colours.

His Themes

- The solitude of the human in front of creation – man a lonely stranger here, yearning for the infinite.

- The inaccessibility of our goal, or of God – man’s lonely quest.

- Beauty in a transient world. The unity between humans, God and nature.

- Death and resurrection.

His Methods.

He travelled round Germany building up a collection of drawings of natural motifs – trees, rocks, mountains, plants, clouds, ships and old ruins. These natural motifs, which he regarded as descriptive surface appearances, were later transfigured in his paintings as symbols of hidden values, or of invisible reality. He believed that the objects we see in the world around us are like cloaks hiding a greater reality underneath, and that we can find this hidden reality by reflection. “The painter should paint what is inside himself, not what is in front of him,” he wrote.

Evergreen trees are symbols of eternal life or the Christian way of life; the sun a symbol of God; the moon a symbol of Christ; mountains, the goal of the romantic quest, are symbols of God. Dead trees or dying oaks are symbols of death; rocks are seen as symbols of enduring faith; the fog, a symbol of our unknowing; the sky symbolising salvation and freedom - the goal of a quest or of a future existence. Ships and boats symbolise the journey of life and its uncertainty.

The close relationship between Friedrich’s way of life – its simplicity, generosity and love of nature as the ultimate refuge – and his art, is evident in all his work.

The relevance of Friedrich’s art for today’s world lies in the realisation, slowly dawning on us, that nature is not simply inert and lifeless, to be exploited and abused, but breathing its own life and spirit. His art is a wonderful revelation of that spirit.

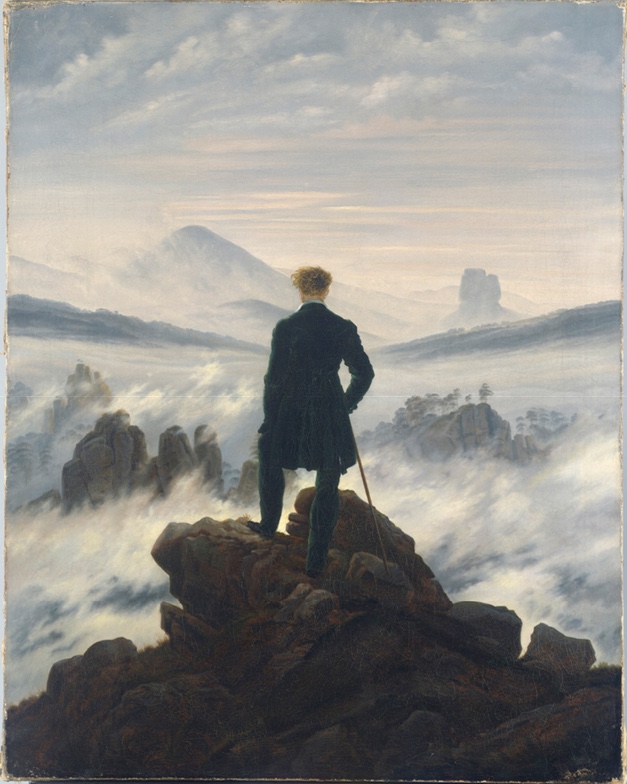

Der Wanderer uber dem Nebelmeer (Wanderer Looking over a Sea of Fog). Friedrich. 30.005.

“When a landscape is covered in fog it heightens expectation”, Friedrich. The Wanderer represents a man, possibly Friedrich himself, standing on top of a high mountain with his back to the viewer. It symbolizes the solitude of man who has reached what he expected would be the ultimate goal of his life while still remaining firmly rooted to this world. A goal may have been reached but there still remains a yearning for the infinite.

The traveller/wanderer has left the fog-enshrouded depths behind him and climbed to the summit. Does this represent his triumph over the struggles of life? The picture is a metaphor for our journey through this life. As we struggle to what we think is the highest peak of achievement we are still confronted with what seems an infinity of mountains still to be scaled as we look across towards an ever extending horizon. How can we really ever get through the mist of uncertainty to reach our ultimate goal and achieve full contentment? Or is this beyond our grasp in this life?

The wanderer’s head is echoed in the crag on the right, symbolizing the unity of man and nature. The mountain peak to which he is turned represents the goal of his quest, the God symbol. The shape of the mountain is echoed in his shoulders, symbolizing the affinity between man and nature.

Winter Landscape 1811, Caspar David Friedrich Schwerin, Staatliche Museum, Germany.

This is a more pessimistic picture, painted during the uncertainties of the Napoleonic wars. Here, the wanderer represents the artist himself, lost as night falls in a wilderness of snow and ice. He passes tree trunks and dead oaks – all reminders of death, and then faces into a frozen lake or sea. The man is overcome by a feeling of hopelessness. There is no sign of a shelter for the night or even a path. Some of the oaks are already hacked down, reminding him of death. There is no light from the leaden dark blue sky above. The old man with his crutches, staggers and falters. The way ahead is closed. This is the end of the line, the end of the road for one man – and for humanity.

Man and Woman Contemplating the Moon. Friedrich, 1829. Berlin, Nationalgalerie

Later on in his career, Friedrich often placed his wife Caroline in his paintings. Here she is with her arm on his shoulder as if seeking support. The couple have paused while walking through the mountain forest at night-time. Darkness envelops them as they gaze at the crescent moon. Trees and rocks acquire eerie dimensions. They now pause and stand beside a mighty pine tree, seemingly rooted to the top of the ridge from where a great gulf separates them from their goal. The stony up-hill path shrouded in darkness, is the path of life. The serene pose of the couple contrasts sharply with the half-uprooted oak tree on their right – an allusion to their deaths or a reminder of the trials and tribulations of life. However, the ridge of evergreens in the distance (missing from the detail) is a symbol of our hope of eternal life. Having reached the top of the ridge, they have eyes for nothing but the full moon, the symbol of Christ. In the Romantic tradition, the moon can represent an inaccessible goal, drawing us on but not enabling us to get there.

The man is dressed in an old German costume, a medieval style of dress which was illegally worn by German patriots. In this, Friedrich reveals his democratic politics during the return to autocratic rule in Europe following the defeat of Napoleon.

In the autumn of 2004 this painting was exhibited in the National Gallery of Ireland with a selection of other works by Friedrich in a special exhibition of German Romantic painting from the National Gallery of Berlin. It is a very dark toned painting. Most reproductions represent it as being much lighter in tone.

Caspar David Friedrich, Moonrise over the Sea, 1822. Nationalgalerie, Berlin

Friedrich would take long walks at daybreak and at sundown, and even into the night. Alone, he strove to penetrate the surface appearance of things and the hidden aspects of nature, pausing to contemplate a special rock on the seashore, a blackened stump toppled by lightning, or an uprooted tree still green with leaves.

Moonlight, for the Romantic generation, was an extraordinary and magical experience. The moon was a theme in philosophy, music and poetry. Friedrich was dazzled by the moon, but there was also something melancholic about its appearance. It drew him into depths of contemplation as if he were searching for another dimension of being. For him, it was a luminous bridge between heaven and earth.

The Chalk Cliffs of Rugen. 1818 Caspar David Friedrich. Oskar Reinhart Foundation Winterthur, Germany.

In the summer of 1818, shortly after his marriage, Friedrich took his young wife on a tour of his homeland, Greifswald, and together with his favourite brother, Christian, they visited the spectacular white cliffs of the island of Rugen. This picture resulted in that visit.

The central figure is the artist himself gazing over the precipice while holding fast to the grass, you could say holding on for dear life. The figure on the right leans against a dead tree stump (a symbol of death), his feet precariously anchored against a decaying bush as he contemplates the scene with the departing boats (symbolising the voyage of the soul after death). The figure on the left is his wife, Caroline, dressed in red, the colour of love.

According to some authorities, the two men represent Friedrich himself. The standing man is the painter looking at nature in its immensity and saying ‘How vast, how mighty, how glorious!’ The man peering at the blades of grass on the edge of the cliff is the other Friedrich, who said ‘Every flower, every stalk is admirable and beautiful because the divine is present in everything’.

Seen thus, the two men are counterparts of the near and the distant. And the woman? She is not excluded from their relationship but expresses her own experience of nature by her gesture. She draws attention to the depth of the abyss between the nearness of the grass and the distance of the sea. Her eyes are closed as if obeying her husband’s instruction to ‘close your physical eye’. This connects her to the standing man who is ignoring that advice for the moment. The trees and branches meeting above can be seen as a heart, making a coded link between the two of them.

An idyllic scene which seems to belie itself, with a hint of melancholy beneath surface appearances? Is he saying that even the simple pleasures of this world are illusory, that they will not last in the face of the reality of death, or is he referring to the precariousness of life, poised as it is, on the edge of an abyss? Is the painting a reminder of death in the midst of happiness? Can we be really happy in this life? The other side of the coin need not always be death. There is often the loneliness of the artist, his fear of rejection and of failure.

Woman of the Setting Sun. 1818. Caspar David Friedrich. Museum Folkwang, Essen, Germany.

This time Friedrich did not eliminate the middle ground, but adopted the classic construction of receding planes. The figure of the woman, dressed in town fashions who has obviously come here on a journey, stands in front of a farmed landscape with rocks, fields and a small church, giving a religious note to the scene. The path on which she stands, symbolising the life-journey, ends abruptly. It is as if thus far she can go but no further. The infinite is inaccessible. She stands alone on the verge of the ‘other world’, far from her everyday cares, like a figure in a dream or a sudden vision. She stands pointing at two rocks on either side of the path as a sign of her belief in eternal life. Her outstretched arms echo the rays of the sun and thus unite the darkest and lightest areas of the picture – in other words, this world and the hereafter.

The coming of the night of death brings with it the certainty of a new sunrise symbolising eternal life. Everything suggests that this picture represents a spiritual landscape in which the woman indicates the way towards the light, the mountains and God. The whole is bathed in a transparent light, in which there is no longer any obstacle, whether rocks, snow or fog, between humanity and the divine presence.

Caspar David Friedrich, Village Landscape in Morning Light, 1822. Nationalgalerie, Berlin.

Village Landscape in Morning light was painted as a companion to Moonrise over the Sea. A shepherd rests against the trunk of a leafy oak while his flock graze peacefully in the fertile plains. Apart from the shepherd who represents humanity, here again are the usual symbols – the oak tree (is it a dying oak, a symbol of death?), the mountains and sky representing God, the goal of the shepherd’s quest, and this time a pool of life-giving water. The middle distance is included indicating that while the shepherd can rest for now, he still has come considerable distance to go on his journey. There are echoes of Psalm 23 in this painting: ‘In meadows of green grass he lets me lie, to the waters of rest he leads me; there he revives my soul’.

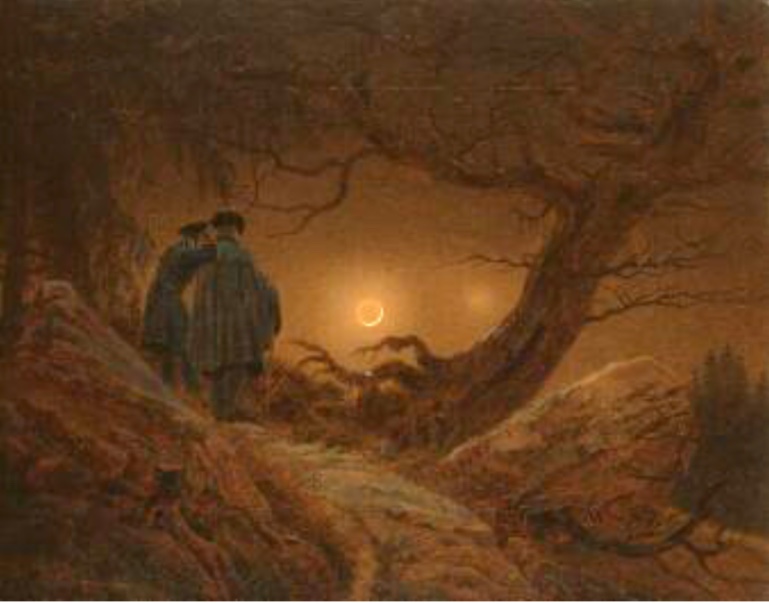

Two Men Contemplating the Moon. Caspar David Friedrich.

This picture glows with an unearthly ethereal light, a painting dark in tone. Friedrich was obsessed with the theme of nocturnal contemplation, the attempt to establish a connection between the terrestrial and the lunar realms. The two men are probably Friedrich and one of his pupils, the young man presumably leaning on the wisdom of the older. The location could have been the cliffs of Rugen, but the most reasonable guess (according to art historians) would be somewhere in the Hartz region which the artist knew very well.

The composition represents the end of a journey uphill through rough terrain (life struggle) to observe the moon and to experience a connection with an infinite and otherworldly cosmos which draws us on but remains beyond our grasp – a reality that lends an air of melancholy to the painting. Can we realize all our dreams? Compare with Wanderer Looking over a Sea of Fog.

Morning. 1820. Caspar David Friedrich. Niedersachsisches Landsmuseum, Hanover, Germany.

Friedrich painted a four-part series showing the time of day. Morning symbolises the beginning of a man’s life. A fisherman pushes his boat out through the mists into the deep, heading off on his uncertain journey through the world, the fog symbolising the cloud of unknowing. On the left are nets hung on poles to dry, implying the daily toil involved in earning a living. The house represents the small area of security that humans succeed in creating for themselves in this world. The fir-trees on the left symbolise the Christian way of life which we need to guide us through this life. The man’s goal lies hidden beyond the mists obscuring the distant mountains.

There are echoes of Friedrich’s vision in the writings of the 19th century American poet, Walt Whitman who looked on the things of this world as miracles and said that “a leaf of grass is no less than the journeywork of the stars –

“And the narrowest hinge in my hand puts to scorn all machinery,

And the cow crunching with depressed head surpasses any statue...

And the running blackberry would adorn the parlours of heaven.“

In a poem entitled Miracles the same poet wrote about –

“The wonderfulness of insects in the air,

Or the wonderfulness of the sundown, or of stars shining so quiet and bright,

Or the exquisite delicate thin curve of the new moon in spring.

These with rest, one and all, are to me miracles.“

“Stand upon the summit of the mountain and gaze over the long rows of hills. Observe the passage of streams and all the magnificence that opens up before your eyes; and what feeling grips you? You lose yourself in boundless spaces, your whole being experiences a silent cleansing and clarification, your I vanishes, you are nothing, God is everything” – Carl Gustav Carus, pupil of Friedrich.

“I must be alone and I must know that I am alone in order to see and hear nature fully. I must be in a state of osmosis with my environment. I must become of the same material as the clouds and mountains of my land in order to be who I am” – Friedrich.

It can be noted that many of Friedrich’s paintings may stimulate a response in creative writing and an awakening to the natural world.

See two further works by Friedrich: Monk by the Sea, 1809/10 and Abbey in the Oakwoods, 1809/10, in The National Gallery, Berlin.