Romanticism

THREE GREAT ROMANTICS.

At this stage we will move back again in time to the early nineteenth century before the arrival of French Realism - to the Romantic era. Romanticism was a reaction to the rigid unchanging world ever since the Renaissance when time seemed to stand still and nothing much had changed for hundreds of years. The lord was in his manor and the peasant was in his field. There was a belief that dealings between humans should be governed by reason in order to ensure stability and permanence.

The age of stability and order ended with the French Revolution and the chaos of the early 19th century Industrial Revolution, both of which brought about a situation of turbulence and uncertainty in Europe.

There followed a sudden desire to break out of the confines of reason. Because man is also a creature of emotion and imagination, there is a tendency to explore beyond the bounds of reason, to launch out into the unknown.

In the capitalist system of the Industrial Revolution there were new opportunities for the individual who would strike out on his own, but while on the one hand there was a fear of the unknown and the threat of failure, there was also the possibility of great drama and excitement.

Highlight

Romanticism was a reaction to the rigid unchanging world ever since the Renaissance when time seemed to stand still and nothing much had changed for hundreds of years. The word ‘romantic’ suggests excitement, joy, discovery, wonder and adventure. It is an emotional response to the world.

As an artist, there was a compelling need to strike out on your own and face an insecure future. After the Act of Union in Ireland, artists could no longer rely on the patronage of the landed gentry, most of whom now lived over in England. This was true in the case of the Irish artist, James Arthur O’Connor. This was also the main reason why he had to move to England to make a living.

Romanticism was also a return to nature, which with the decline of the official church, had become a kind of new religion. The squalor of life in the new industrial towns had left people with a yearning for nature. This move back to nature is reflected in the art of the Romantics.

CHARACTERISTICS OF ROMANTICISM.

Romantic art is an expression of the dramatic struggle between man and nature. It places heavy reliance on emotion, drama, insecurity and unease in the face of the unknown.

There is great excitement, an urge to explore, to launch out into the unknown, to confront danger. There is a lack of clarity because the outcome of the journey is unknown. An emphasis on tone and tonal contrasts accentuates the mood of drama and conflict. The tonality is often dark and foreboding, gloomy and melancholic Nothing is clearly defined. Where people figure in Romantic art, they appear dwarfed and engulfed by nature. Their journey is very much a leap into the unknown. It could be terrible but also wonderful.

The urge to move out, to explore and to conquer nature was the main preoccupation of the 19th century, and in this, art reflected life. Romantic art is said to be naturalistic rather than realistic. There was no question of the artist setting up his easel and painting the scene in front of him, as was the case with the Impressionists.

Although gloomy and melancholic, there is some optimism in the work of the Irish artist, James Arthur O’Connor. However, the English artist, William Turner inclines towards pessimism. His dominant theme was the powerlessness of man in the face of wild, threatening nature.

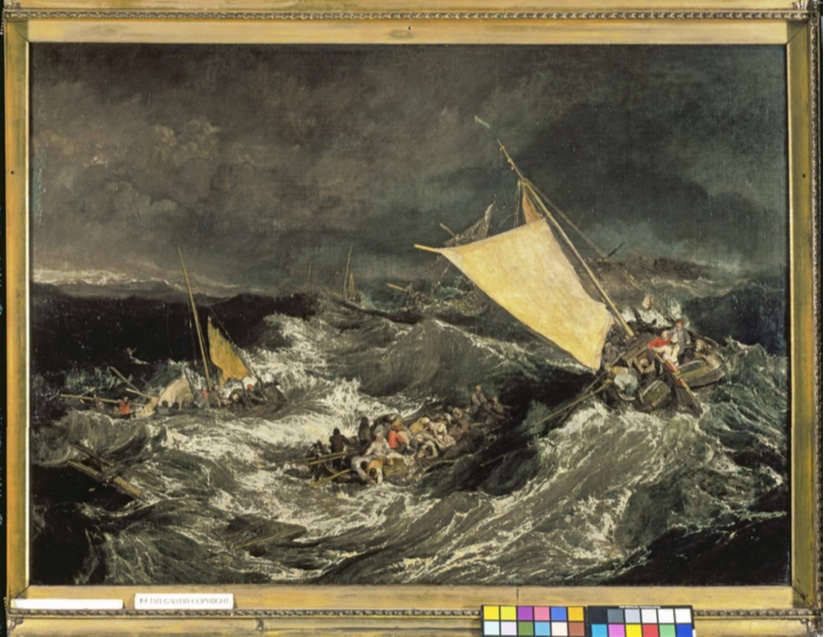

His response to nature is one of turbulence and wrath. In his painting, Hannibal Crossing the Alps, 1812, Tate Gallery, London, where Hannibal and his army, symbols of the fate awaiting all humans, are overwhelmed by a sudden avalanche thundering down the mountains. The mood is dark and sombre, wild and threatening. A similar atmosphere of threat and foreboding is evident in The Shipwreck (image page 54) where the ships are about to be engulfed in a whirling maelstrom of sea and sky. But Turner could also have his moments of enchanted serenity and tranquillity as in Petworth Park: Tillington Church in the Distance, William Turner. Here in a departure from his usual dramatic contrast of light and dark we find a harmony of warm colours, a pattern of vertical and horizontal lines accentuating the mood of peace and calm as the shepherd returns home (symbolic of a place of rest) with his flock.

As a contrast to Turner, in the work of the German Romantic artist Caspar David Friedrich (see Chapter 9), there is a yearning for the infinite, and because of this, nothing is clearly defined. Friedrich expresses the wonder and awe he feels in the face of nature. His response is one of silence and calm. To him, the elements of the natural world are symbols of transcendence. Friedrich is something of a mystic who tries to peer into the unknown and uses his art to reach out beyond the confines of this world.

In the next section we will have a look at some of the work of the Irish Romantic artist, James Arthur O’Connor.

IRISH ROMANTICISM - JAMES ARTHUR O’CONNOR.

The Irish artist, James Arthur O’Connor, was born in Dublin in 1742 and died in London in 1841. His landscapes are dark and foreboding, their horizons frequently obscured, with only a hint of blue sky, which seems to beckon invitingly from behind sombre trees or high inaccessible rocks. The terrain is rough and untamed and man is portrayed as an intruder or stranger. There is often only one person, which serves to emphasise the mood of isolation – man alone against the world, dwarfed by nature, engulfed in the drama and excitement. His emphasis is on dark tones and sweeping turbulent movement.

Not for him the horizontal lines expressing the clarity and calm of classical painting. Observe the high drama wrought by the dark sinister forests, towering rocks, billowing thunder clouds, roaring torrents and windswept trees in Thunderstorm: The Frightened Wagoner.

The thunder and the bolt of lightning is echoed in the sharp rock face, in the menacing tentacles of the branches of the wind-swept tree in the foreground and finally in the wagoner and his horse. Whether the eye turns first to the tree, to the cascading waterfall, or even the bolt of lightning, our attention is drawn to the centre of the picture, also the area of greatest tonal contrast – to the wagon-driver, alone and afraid.

The wagoner is the focus of the painting in every sense. He stands, perhaps as a symbol of the artist himself as he embarks on his uncertain journey through life.

We too can identify with him in our own fears and struggles. Is the bolt of lightning symbolic of all the sudden disappointments, perhaps accidents or any of the unexpected turns of fortune that suddenly assail us? Then the bridge ahead is suddenly down and we are not certain if we can go on or have a wish to do so.

The whole painting is symbolic of the inner struggle of the artist, caused by the pull on the one hand, to cling to the security of his traditional patrons in Ireland, and on the other, the need to express his anxiety, fear and uncertainty as he sets out to make his own way in the world. Does this painting represent optimism or pessimism?

In The Poachers the emphasis again is on tone, a clear image of rolling hills under a beautifully lighted sky set against a navy blue background. This is Romanticism in all its wonder and magic.

Like the Wagoner, the three poachers are also on a journey. With shadows cast behind them, they stand in the centre of the picture, framed on the left by a clump of trees and on the right by a bank of bushes. Directly above them is the bright moon, encircled by clouds.

The eye is led into the picture by gradations of tone, the darker tones in the foreground. Everything is unified by the light. Three men out for an evening stroll, a calm and tranquil scene, on the surface, almost classical in quality were it not for the sudden movement of the moon from behind a cloud, which introduces the element of drama and excitement. It should be remembered that the penalties for poaching were severe in 19th century Ireland.

Here, as the three men go about their furtive business, the surrounding shadows hiding their movements, and like the bolt of lightning in the last picture, the unexpected happens when the moon suddenly emerges from behind a cloud, exposing them to danger. There they stand, frozen in their isolation, fearful and apprehensive. Will they turn back or go on? Here again, it is a case of nature, the world, life conspiring against the individual who is seen as an intruder. Good for a response in creative writing.

There could be a comparison drawn between O’Connor’s two paintings. In what way are they alike, different?