Expressionism

The Post-Impressionists, were deeply indebted to the Impressionists for their use of bright colours, but they disagreed with the Impressionist aims of recording the transitory effects of light and colour. They sought to create a more expressive and more individual kind of art. The post-Impressionists never formed a group like the Impressionists. They branched off in different directions, Van Gough, for example into Expressionism, Seurat and Signac into a movement known as Pointillism.

The Expressionist movement originated around the turn of the century as a reaction to the rather impersonal character of Impressionism. It was felt that the materialistic ethos of the Impressionist era no longer reflected the current realities of alienation brought about by the scientific and industrial revolution in the years before the First World War. Part of the reason for the shift of emphasis was because of temperament. The mental outlook of men like Van Gough and Munch was far removed from the casual, happy-go-lucky attitude to life of the Impressionists who acted and worked as a group, sharing their ideas. The Expressionists no longer felt themselves as part of society, but as lonely, isolated individuals making their own way in the world. Furthermore they came from a northern more hostile environment, as against the easy going Mediterranean world. In such an environment God goes out of nature. Man is alone with his feelings.

No longer content with recording realistic impressions of the external world in an impersonal manner, the new artists now rejected the notion of basic harmonies in nature and between man and nature. They would hold, that this harmony, if it ever existed, had been disrupted by human folly and they no longer saw themselves as members of society but as isolated individuals with an inner life of their own, crying out in resentment and horror against a hostile world.

Highlight

The Expressionist movement originated around the turn of the century as a reaction to the rather impersonal character of Impressionism.

The Expressionists then concentrated on the expression of strong feelings of tension, anger, sadness, isolation and alienation, felt by the artist in a world where he no longer felt at home.

The Expressionists then concentrated on the expression of strong feelings of tension, anger, sadness, isolation and alienation, felt by the artist in a world where he no longer felt at home.

With the exception of Van Gough, the Expressionists did not paint outdoors because to them the world was hostile and oppressive. God had gone out of nature.

THE ART ELEMENTS IN EXPRESSIONISM

Colour

The Fauves were the first to free colour from the object. As with the Impressionists and Fauves, Expressionist colour is pure and intense, (the Impressionists having once and for all released the genie of colour from the bottle), but there are differences. Black and red are more frequently used with symbolic intent, black to symbolise grief or death, and red to suggest anger or violence. Complementary colours are juxtaposed to convey a violent effect – red clashing with green, orange against blue, yellow and purple. There are strong contrasts of cool and warm colours. Harmonies generally, are less in evidence. Contrasting colours are placed side by side for a violent effect. Where Fauvism tended to be merely decorative in a wild sense, the Expressionists concentrated on the strong expression of feelings, and to this end, their use of colour, line, texture and form differed from the Fauves.

This tension and expression of strong feelings is mediated by the distortion of the art elements, especially, line, colour and form, often to such an extent that the distortions go beyond the point where we can accept the possibility of objects existing as the artist represented them.

Line

Shape and line are also distorted. There is distortion of the human figure to show dehumanisation and alienation. There is a strong emphasis on line. Line can be wavy, jagged, hard, strong, heavy and often black. Diagonal line expresses rapid movement. See The Scream, by Munch. The works of Van Gough illustrates how the use of wandering, restless line can express his moody, tempestuous world. See his The Starry Night and Olive Trees. In Olive Trees, the twisted and bent trees are expressive of his inner turmoil. In these paintings, line is said to be active.

Tone

The even tonality of Impressionist painting is no longer in evidence, giving place to sharp tonal contrasts. Colour and tonal contrasts, with distorted line, combine to create a jumpy, clashing mood of unease and uncertainty.

Shape and Form

There is distortion of the human figure in order to express a feeling of dehumanisation. For examples of this, see the works of Edvard Munch.

VINCENT VAN GOGH

Van Gogh was a native of Holland, a northern, more hostile environment, where man is alone, isolated with his feelings. In order to express these feelings, the artist must distort nature to make it look monstrous and threatening. The artist is not now painting what he sees but what he feels. Colour is symbolic rather than descriptive.

Van Gogh stands as a bridge between the world of Impressionism and Expressionism. He began late in life as an artist in his native Holland. Probably because of his own life of poverty, his sympathy was with poor peasants he saw toiling in the fields. Much of his early work consisted of drawings and paintings of these people. Even when he drew or painted a pair of worn boots he was able to invest them with human feelings. His masterpiece from this period was The Potato Eaters, 1885, Vincent Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam. This is a dark, sombre painting of a group of peasants seated round a table eating a meal of potatoes, their rugged hands and features smelling of hard, backbreaking work. However, the highlights from the lamplight help to create a feeling of intimacy and warmth. At this stage of his career, his emphasis was on tone rather than colour.

Highlight

The artist is not now painting what he sees but what he feels. Colour is symbolic rather than descriptive.

In his early work, Van Gogh was influenced by the Realist tradition of Dutch painting which was also part of the French Realist movement going back to the middle of the nineteenth century. Until he came to Paris he had never seen any of the work of the Impressionists.

Vincent’s brother, Theo had been working in Paris for a firm of picture dealers but it was not until Vincent joined him in 1886 that he actually saw the work of Monet, Renoir, Degas and Pissarro and realized what the Impressionists had achieved. This made a great impression on Van Gough. Immediately, he set about painting the usual Impressionist subjects of Parisian street scenes. The discovery of the bright light of Paris and bright sunny colours was a revelation to him and he continued to use them almost until his death. While in Paris he was also influenced by Seurat and painted some pictures in the pointillist manner.

THE ARLES PERIOD.

Van Gogh soon absorbed all the Impressionists could teach him and he became restless once again. Once he had learned the new techniques, making pictures that were merely dispassionate visual records no longer appealed to his fiery temperament. After he left Paris in February 1888 to paint in the south of France his work became more and more personal, ensuring his place in art as the leading post-Impressionist and the forerunner of the Expressionists.

Springtime in Arles was a revelation to Van Gogh. Suddenly the fruit trees exploded into blossom. He quickly set about painting several pictures of orchards in full bloom. His paintings, after his arrival in Arles, were in the Impressionist mould. At that stage he was happy, making a new beginning in the wonderful light and colour of his new surroundings. As a consequence, his first paintings in Arles - The Peach Tree in Blossom being one example - were celebratory, characterised by the bright even tonality of the Impressionists, with their dabs of broken colour. However there is evidence of a stronger, less atmospheric line and more intense colour.

Van Gogh soon learned that far from depicting nature in a realistic manner, his task as an artist, while still taking inspiration from the scene before him, was to project his own feelings on to the subject to such an extent that a painting of a tree for example, could be almost in the nature of a self-portrait.

He accomplished this by the distortion of colour, line and form. First of all, he began to use colour symbolically to express his feelings, and by juxtaposing violent, contrasting colours to express inner conflict, he found a new visual language.

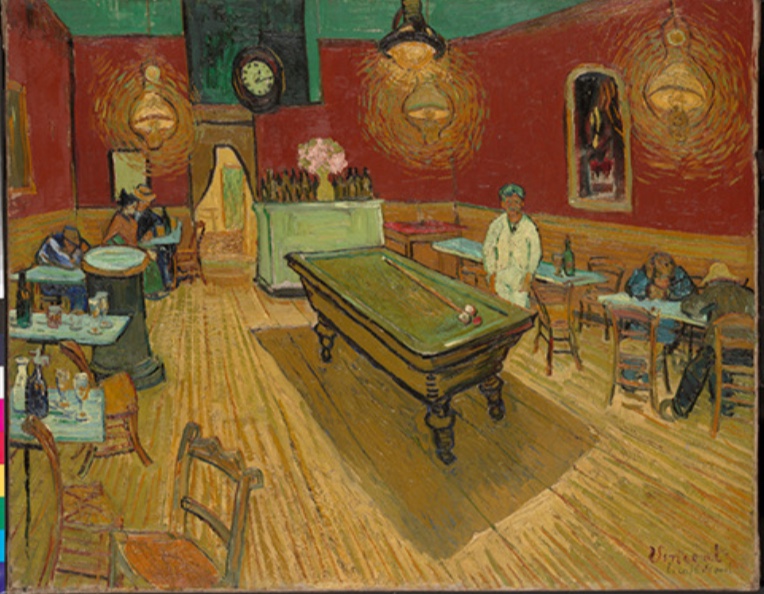

In writing to Theo about his painting, Night Café, he said that he had “tried to describe the terrible passions of humanity by means of green and red.” This painting was in stark contrast to the sunny innocence of the orchard paintings. The café was transformed into a place of dread, fear and unhappiness.

Here, he portrays a closed claustrophobic world of conflicting emotions. The colour is not descriptive but amplified to express feelings. There is a clash of green and red to express inner conflict. The colours in all probability don’t relate to the objects in the room.

In his expressive use of colour, the paint seemed almost thrown on to the canvas as if in a fit of anger, hurried brushstrokes giving the work a crude finish and creating a disturbing mood. Gone forever were the days when a painting had to look beautiful, probably emphasising the point that for many people life is not beautiful.

Night Café, Vincent Van Gogh. Yale University Art Gallery.

His next innovation was in the use of a wandering, wavy line which distorted landscape features and expressed a restless, unstable nature. His plunging perspective, as evidenced in Night Café, for example, gave an impression of his isolation in a hostile world that he felt increasingly closing in on him and from which there would be no escape. All along he had to depend on his brother to support him financially, and his work was never recognized during his lifetime. To make matters worse, he was shunned by the locals in Arles as a mad eccentric.

The café appears a sad and lonely place. The low-life characters, small and insignificant, slouched over tables, hiding away round the edges of the room, emphasising the feeling of emptiness and loneliness, isolated from each other and from the world.

There is no communication between them. They might well be in some prison from which there is no escape. But in a sense, they are self-portraits. The billiard table in the centre of the room is deserted. There is no fun here. The distorted plunging perspective gives a sense of things closing in. Objects in the room, like the row of bottles, have taken on a human dimension, looking like a line of convicts marching to their death. There is a shimmering tension in the orange and green halos surrounding the lamps. Even the landlord with his staring eyes seems to threaten the artist as he paints. Not a pretty picture. He himself said it was ugly. In a letter to Theo, he described it as a devil’s furnace.

This room could be a symbol of the human condition, of his own loneliness and isolation, a symbol of the world as he saw it.

In a reproduction of this painting in particular, it is only through an actual size detail that we can appreciate the rough hewn texture and the rapid and reckless brushwork employed by the artist to portray the predicament of the two down-at-heel characters slumped over the table in a corner of the room. Texture and colour, and paint applied with abandon in order to express strong feelings. Although the faces of the characters are hidden from our view, we are still aware of their feelings. Can hopelessness or despair be expressed by a back?

Note how Van Gogh depicts a shoe - an unimportant detail in the over-all scheme of things - with one twirl of the brush. We are aware how children can get bogged down in technique in their painting activities when all that matters is abandoning all inhibitions in the attempt to express their feelings. A discussion of this painting should help in that direction. Any discussion of a painting such as this with children should conclude with an effort to relate it to life experience. That too will be helpful in their immediate follow-up work.

For discussion purposes, compare this painting with one by Renoir where crowds of people enjoy each other’s company. See The Swing and Le Moulin de la Galette, by Renoir.

THE SAINT-REMY PERIOD.

Ever since Vincent came to Arles he had an ambition to form a community of artists in the south. He had hoped to be joined by Paul Gauguin and his friend Emile Bernard, both of whom he had known in Paris. Eventually, Gauguin arrived in October, 1888. They both lived together in the Yellow House. They painted the same subjects outdoors and all went well for a while.

However after some time, and due to a clash of temperament and different views on art, Van Gogh's frustrations built up as he became disillusioned over his quarrelling with Gauguin. That was bad enough until Gauguin threatened to leave. On 30th December 1889 an incident occurred between them that led to Gauguin's departure and Vincent's breakdown. After a while in the hospital in Arles, he appeared to have recovered completely. On 7th January he was allowed back to the Yellow House, where he began to work again. Two self-portraits from this time show him with a large bandage covering his mutilated ear. Then in February Van Gough had another breakdown. But this time his neighbours were determined to rid themselves of the 'madman' in their midst and petitioned the mayor, demanding that he be sent back to his family or confined to an asylum.

After another spell in the local hospital he was well enough to paint again and continued to work away until May 1889, by which time he realised he could no longer care for himself and expressed the wish to be admitted to St. Pauls, an asylum in Saint- Remy, twenty seven kilometres north of Arles.

While in Saint-Remy he was well enough to paint despite some intermittent attacks. It should be noted that the diagnosis of many of the doctors who treated Van Gogh was that he suffered from epilepsy and the prescribed treatment for this while he was in Saint- Remy was cold baths two days in the week.

There is a marked development in his style now. All the elements of nature are fused into a whole as his brush-strokes move all over the canvas, running, heaving, curling, swirling and flaring, filling everything with the pulse of life, as he painted wheatfields, olive groves and cypresses.

The Starry Night. Vincent Van Gogh. Museum of Modern Art, New York.

It was here in Saint-Remy he painted one of his most transcendental visions – representing his effort to reach out beyond this space and time to something awe- inspiring, something we can only dream of or imagine - the wonderful, The Starry Night.

In The Starry Night, he sees the world as full of wonder and magic. For Van Gogh, the world was both terrible and wonderful, terrible because of the reasons outlined above, but wonderful, because Van Gogh loved nature. This mental conflict is evident in all his art.

In this painting, swirling, wave-like nebulae fill the night sky. A cypress tree and the entire landscape tremble and move in sympathy. Only the little village remains solid in the turbulent vastness of the universe.

Here, nature is both terrible and wonderful. The yellow light of the stars is echoed in the lights of the little houses in the village, linking the world of humanity with the heavens. This painting is full of a sense of joy at the harmony between the tiny world we know on earth and the vast expanse of the universe, which is at once threatening and beautiful. The beauty of the colours sings out in his balance of orange and blue. The universe is vast, awe inspiring and full of life, wonderful.

However, nature is also terrible. There is distortion of line and colour to express tempestuous feelings. Through the use of flowing, wavy line, indicating rapid movement, it seems as if the whole universe is about to rush across the sky and like some great river, sweep down to overwhelm humanity. There is the clash of orange and blue. Nature is distorted to make it look threatening.

Contrasting line provides another element in the conflict. The cypress tree on the left, twisting its tortuous way upwards as a counter movement to the rush of the comets, probably symbolises the artist himself, a solitary figure, rising up, but still bowed down by the pressures of life, as he bravely and defiantly points his finger at the heavens closing in on him. The edge of the hills and the trees are on the same headlong rush, surging and swelling around the houses, threatening to break down and engulf all as if a mighty river. There is a feeling of no way through, no escape from the catastrophe. Diagonal line in this part of the painting, serves to heighten the flow of movement.

The steeple of the tiny church, acting as another vertical thrust, tries to hold back the headlong movement of the lines forming the hedges and mountain contours. The contrasting vertical lines act as elements in an effort to bring some stability to a world in chaos.

The painting is a wonderful example of harmony and contrast of colour and line. Good for a response in creative writing.

Van Gogh longed for the peace and rest he thought he could find in a home and family life. This was a goal that eluded him all through his life. At the same time he was aiming literally at the stars in an uncontrollable drive to express himself through art. The conflict between these two aims must have affected his mental health. He was aware that his art, although unrecognized in his lifetime, would be his lasting contribution to humanity. His tragedy was that he also knew that it was slowly killing him. His courage was evident in his dogged persistence against all the odds and in his refusal to compromise.

Meanwhile in St. Pauls, the attacks were becoming more frequent and lasting longer. In correspondence with Theo he stated that he would like to move to the Paris area. Theo agreed to make arrangements. While he was doing so, Vincent resumed his painting with renewed enthusiasm.

Landscape with Olive Trees, 1889. Museum of Modern Art, New York. John Hay, Whitney collection.

In his gloomy Landscape with Olive Trees, the tumult of interconnected, undulating line and curving brushstrokes binds together sky, hills and trees into a dramatic whole. Now his colour has grown darker and more sombre. The dark, threatening hills in the background weigh over the bent and twisted olive trees below (symbols of the artist himself?), almost crushing them to the earth. These works couldn't look more unlike photographs. They are revelations of Van Gough's mental state, disguised in landscape.

Road with Cypress and Star. June 1889, Otterlo, Rijksmuseum, Netherlands.

This was his last landscape painted in Saint-Remy. Romantic' was the word Van Gough used to describe this painting. The picture has echoes of The Starry Night in its attempt to set up harmonies between heaven and earth. The short brush strokes twist and wind their tortuous way through the picture, turning the whole surface of the canvas into a blaze of fiery energy. The sky swirls and twists in all directions.

Two travellers, followed by a cart, appear as if about to be swept away as the road tumbles down to swamp the wheat field and cypress. The crescent moon, the sun and a solitary star carry haloes of energy in an infinity of sky pierced by two twisting cypresses. But in its plunging perspective and ambiguous portrayal of space it reflects Van Gogh's mental state as he sets out on his final journey, following on his comment that 'we take death to reach a star'. Does he foresee a situation where he too will be swept away in some turbulent tide like the two travellers and the cart?

The last painting done shortly before he left Saint Remy, was a self-portrait, Paris, Musee du Louvre. 'My surroundings here begin to weigh on me more than I can express. I feel overwhelmed with boredom and distress,' he wrote to his brother from the asylum around this time. This self-portrait expresses some of the agony and anxiety of that claustrophobia.

Van Gogh left the Saint-Remy asylum in May, 1890. He had begun to feel increasingly nostalgic for his homeland. He was beginning to tire of the southern sun, and the more subdued greys, greens and browns that he had last used in Holland began to reappear in his landscapes.

THE AUVERS PERIOD.

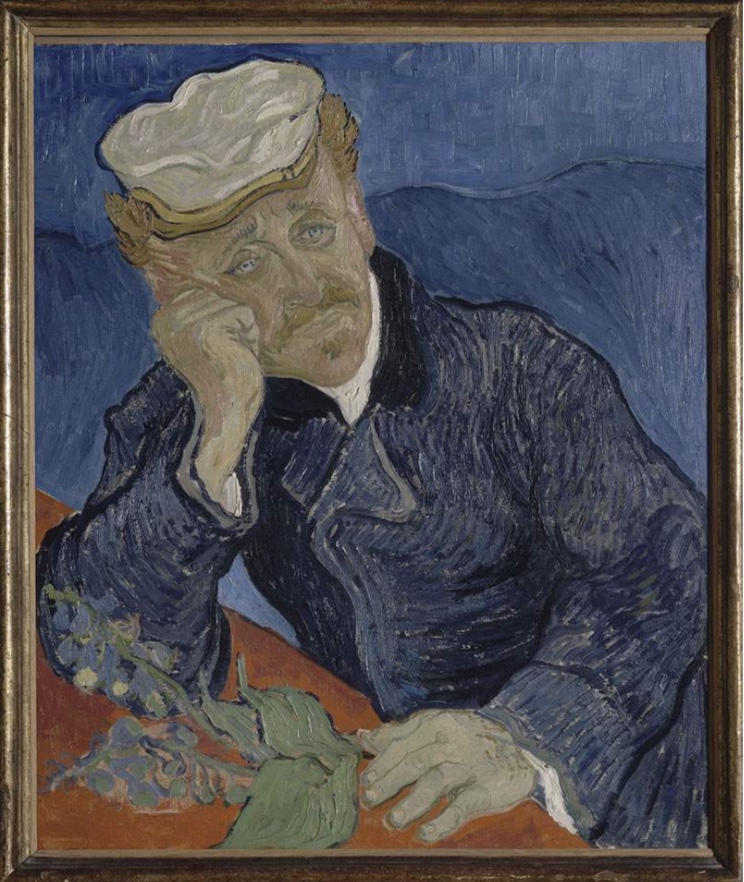

He spent a few days in Paris with his brother, now married and with an infant son, also named Vincent. While in Paris arrangements were made for Vincent’s move to Auvers-sur-Oise, a pleasant little village outside Paris. There he would be under the care of Dr. Paul Gachet and live in lodgings. Dr. Gachet was a sympathetic man, an amateur artist and collector of Impressionist paintings. He was aged sixty-one and a widower. He believed that the best therapy for Vincent was the freedom to carry on with his art. As a socialist and freethinker, the doctor had spent his youth frequenting the Bohemian cafes of Paris. Now in his middle age he spent most of his time in his gloomy house among his antiques and paintings, perhaps dreaming of his lost youth. After the inmates of Saint- Remy, Gachet was a welcome companion for Van Gogh, whom he saw as a disappointed and isolated man. Are these feelings expressed in the Portrait of Dr. Gachet? The pose he is placed in, with head resting on hand, is the traditional one of the melancholic. Do the dark, sombre blues express sadness? Is there an expression of sadness in the sitter’s eyes? Does the swaying background seem claustrophic? This portrait is considered to be one of Van Gogh’s finest paintings.

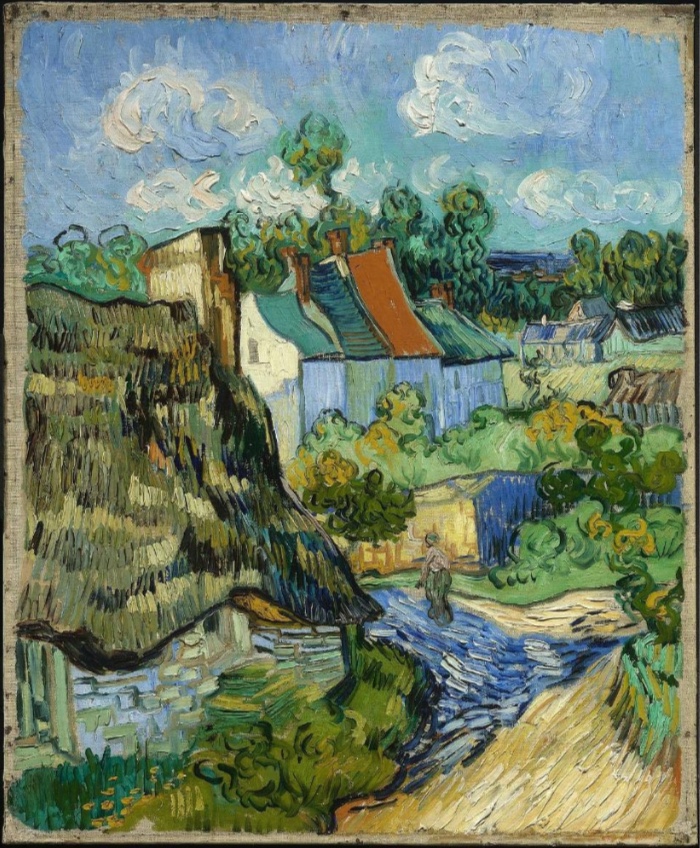

The beautiful countryside around Auvers inspired Van Gogh, who began to work with furious energy, rising each morning at five and painting all day with a short break for lunch at the café. During his seventy days at Auvers he completed over eighty canvases, many showing signs of an almost desperate haste as if he knew that his time was limited. He was attracted to the thatched roofs and tumbled cottages of the villagers and views of the surrounding countryside, much of his work with that 'unfinished' look of his final period. His style and handling of paint varied, from the decorative to the wildly expressive. He was glad to leave the southern sun behind him. His colour now became less bright and more sombre. See his View of Auvers, Tate Gallery, London. Again, as in all his work, everything is distorted for expressive purposes - the twisted trees, the sagging rooflines of the cottages and the swirling skies.

Despite a visit by Theo, his wife and young son to Auvers in June, Vincent's inner sadness re-appeared in a letter soon after to his mother and sister, expressing his sense of isolation and loneliness. The visit probably reminded him of what he missed most in his life - the simple pleasure of a home and family. In addition, his sudden awareness of Theo's new responsibilities with his wife and young child might mean the end of his regular financial support. Another source of worry for Van Gogh at this time was the news that his work was beginning to attract some critical acclaim. This might seem surprising but Van Gogh was so institutionalized in his role as the despised and suffering servant he would probably look on any change as a threat rather than an opportunity. With all of these pressures mounting up, it is not surprising that he wrote to Theo, 'The prospect grows darker, I see no happy future at all'.

For discussion purposes, Houses at Auvers. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, makes an interesting comparison with Thatched Cottages at Cordeville. 1890. Orsay Museum, Paris. This is a more calm, a happier landscape then the former. Here we have a sunny day in June or July, with puffy white clouds in a blue sky, as against the dark threatening sky and the turbulent line of the other picture. This is a peaceful village integrated into the surrounding countryside, the thatched roofs helping to tie together the man-made and natural worlds. As an aside, in his first letter to Theo from Auvers, Vincent noted that thatched roofs were “getting rare.”

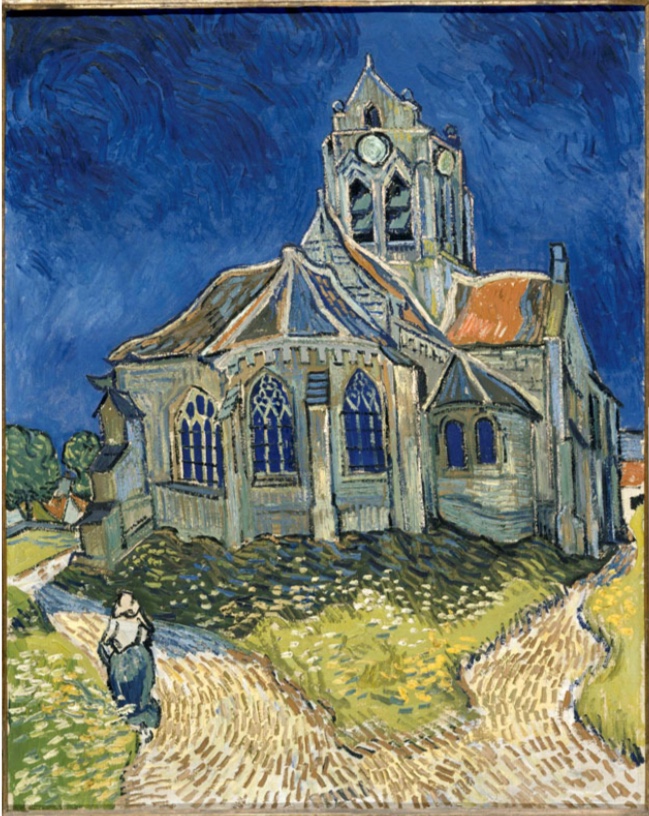

Church at Auvers 1890. Orsay Museum, Paris, (see illustration below)i s another example of his sense that things were closing in on him. The church seems caught in a vice between the opposing forces of the deep purple of the sky and the yellow of the earth. The ominous colour of the sky, weighing heavily on the church, crushing and bending the roof, while in a counter thrust, the earth seems to heave the building skywards, as if representing some inner conflict. The church seems to represent the artist himself caught in a vice between forces over which he had no control. The snaking, diverging paths bypass the building which seems to offer no sanctuary. Does the fork in the road represent alternative paths to salvation? A woman, as if attempting to escape the whirlwind, hurries up the pathway and away from the church to a cluster of red-roofed houses, probably her home. For Van Gogh there was no home, no resting-place.

Early in July he received a reassuring letter about continual support from Jo, Theo's wife. This cheered him up and in a reply he went on to describe the three big canvases he had recently painted. 'They are vast fields of wheat under troubled skies, and I did not need to go out of my way to try to express sadness and extreme loneliness'. The pictures capture the panoramic views of the plain from above Auvers, as in Rain above Auvers, in which he returned to the same sombre colours of his early period in Holland. Perhaps some of his sadness derived from Theo’s troubles at this time. Theo and Johanna were worried about little Vincent’s health, although the doctor had assured them that they were not going to lose him. Theo was also preoccupied with his financial difficulties and the thought of setting up business on his own. The result was that Vincent felt he had no guarantee of his brother’s continued financial support. Despite this, we cannot be sure that Van Gogh’s breakdown at Auvers had anything to do with the strains caused by his relations with Theo and his family.

Wheatfield with Crows. 1890. Van Gough Museum, Amsterdam.

This is probably one of Van Gough’s ‘vast fields of wheat under troubled skies’. We cannot be too sure if it was his final work. It bears comparison with Harvest, The Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam which was painted in Arles, June 1888. The latter was a painting full of human presence and open spaces, with its details of fields, corn stacks and farm buildings stretching back to the distant mountains.

In Wheatfield with Crows there is a sense of foreboding, with no details of fields, buildings or any sign of human presence. The space is closed and claustrophobic. There is no attempt to convey distance through atmospheric perspective. The colours reflect what Van Gough felt rather than what he saw. Here, Impressionism is finally buried. Instead of the tranquil horizontal lines of the Arles painting, the countryside is full of great agitation. Waves and whirlwinds form between earth and sky. Compared with the relatively smooth, quiet surface of Arles paintings, the textures here are rough and agitated, showing rapid execution. Each stroke of the brush clashes with another. There is a violent clash of orange field and deep blue sky. In the sky, two clouds swirl, stirring up a storm. A diagonal line of black crows is seen heading for the foreground like a threatening river. Symbols of approaching death? Two diverging pathways seem to be attempting to scale an almost vertical slope, acting as a counter-movement to the crows. The paths seem to stop midway as if crushed by the leaden weight of the sky. There is no way through, no escape. Opposing forces of colour and line. The only unifying elements are the visible strokes of paint and the uniformly intense colour, indicating intense feelings.

At this time Van Gogh felt only fatigue and a great sense of emptiness. Overwhelmed by despair, he returned to these same wheatfields some weeks later to try to end his life.

We cannot be sure that he had any breakdown at Auvers. Nobody there noticed anything out of the ordinary about him. He was welcomed in Dr. Gachet's home like one of the family. It seems that, even if low-spirited, he behaved relatively normally until the day he decided to end his life. On Sunday 27 July. He left the Ravoux café after lunch with his painting gear for the wheatfields. The pistol shot, aimed at his heart, missed its target but left him fatally wounded. He struggled back to his lodgings and died two days later in the arms of his brother. Before he died he was heard to remark, 'The sorrow will last forever'.

At his burial Dr. Gachet made his final farewell. He said of Vincent: 'He was an honest man and a great artist. He had only two ambitions, for mankind and for art. Art he loved above everything. And it ensures that he will live'.

Sometime after the funeral, looking through Vincent’s possessions, Theo found an unfinished letter in his jacket pocket in which he affirmed that Theo was more than a ‘simple dealer in Carot’s paintings’ but had his part ‘in the actual production of some canvasses which will retain their calm in the catastrophe’. This might have seemed generous enough but it actually implied that Theo’s profession as an art dealer was of no great consequence, and that he should have followed Vincent’s example and become an artist.

Theo was overcome with grief. A parting shot like this from the brother he had loved and supported was too much to bear. He was also blaming himself for Vincent’s final breakdown on having made too much of his own troubles on Vincent’s last visit. Following Vincent’s death he tried to assure the safety of any paintings held by relatives and attempted without success to organize a memorial exhibition. By the time the first such exhibition was held in 1892 Theo was already dead. Six months after Vincent’s death he died of a kidney infection that seems to have triggered a mental breakdown. The two brothers now lie side by side in Auvers.

Harvest – The Plain of La Crau, 1888. Vincent Van Gogh Vincent Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam.

One of the finest of Van Gogh’s southern paintings, Harvest, expresses the calm of the Provencal countryside under the hot summer sun. The contrast with Wheatfield with Crows couldn’t be more striking. Instead of the claustrophobic landscape of the latter we are presented with a vast open panorama of great depth. This picture is life affirming: men and women at one with nature, busily harvesting the food that sustains life. Instead of the violent clash of contrasting colours everything is in perfect harmony, contrasting blues being kept to a minimum. Compare the skies in both paintings. The sky in Wheatfield with Crows moves from deep turbulent blues to a calm airy blue in the southern painting. Wheatfield with Crows has line moving in all directions. In Harvest an atmosphere of calm is created by a number of horizontal lines running across the picture. Van Gogh described the area around Arles as “this flat landscape where there is nothing but ... infinity ... eternity.”

Incidentally, the old monastery nestling under the mountains in the top left corner of Harvest and the plain in front of it can be seen stretching away from the town by climbing to the top of the ancient Roman amphitheatre in Arles.

ohanna Van Gogh became the guardian of the greatest collection of Vincent's paintings and she set about establishing his reputation. By the early years of the twentieth century, avid collectors were hunting down the canvases he had given away, and a new generation of artists had acknowledged his influence. By the 1920s he was world-famous. Theo's son, Vincent, spent his life gathering his uncle's works together.

Highlight

Van Gogh introduced a more humanitarian subject matter into painting, moving away from the bourgeois world depicted by the Impressionists and their materialistic values.

Johanna made the first translation into English of Vincent's letters written to Theo. Van Gogh’s letters have been published. They show an extraordinarily articulate man, a man of considerable literary accomplishment, anything but naïve and crazy. They show him as a man very much in control of his own destiny for all but a few weeks before his death. Above all he was a man who committed himself to his work and his beliefs to the highest degree. “How difficult life must be”, he wrote to Theo in one of his earliest letters, “if it is not strengthened and comforted by faith.” And just a few weeks before his death he was able to say: “I still love art and life very much indeed.”

The letters, drawings and the family's store of his paintings, form the priceless core of the Vincent Van Gogh Foundation in Amsterdam.

Van Gogh introduced a more humanitarian subject matter into painting, moving away from the bourgeois world depicted by the Impressionists and their materialistic values. His influence on the next generation of artists was significant.

EDVARD MUNCH 1862-1943.

The last of the great Post-Impressionists was Edvard Munch. He was born at Loten, north of Oslo, then known as Christiania, the son of an army physician. While still an infant, his family moved to Christiania where he grew up. When he was five years old his mother died of tuberculosis. His sister Sophie, died of the same disease aged fifteen and his sister Laura became mentally ill. His father grew puritanically religious after the death of his wife, often pacing up and down the room reciting prayers. He suffered from remorse and depression, his behaviour at times bordering on insanity. 'Illness, madness and death were the black angels that kept watch over my cradle and accompanied me all my life,' Munch later wrote. No wonder he painted death and disease so frequently, themes based on his personal experience. His father died in 1889.

In 1880 Munch decided to take up the study of painting and he was to a substantial degree a self-taught artist. The Sick Child, 1885, (National gallery, Oslo), was one of his earliest Expressionist paintings.

In 1889 he went to Paris, visited the Louvre and saw Impressionist paintings. He studied in Paris for two years where he often suffered from loneliness and ill health. During this time he also became familiar with the work of the Pointillists and other post- Impressionists.

In 1892 he accepted an invitation to hold an exhibition in Berlin. So shocked were the public and the more conservative artists there, that the exhibition had to be closed down after a week, but because of this he had gained a certain notoriety as a result of which he was invited by art dealers who arranged exhibitions of his work in various German cities. From the admission charges he derived a small income that compensated a little for the meagre sale of his pictures.

During a three-year stay in Berlin he painted many of his Expressionist masterpieces, including The Scream, often returning to Asgardstrand on the Oslo Fjord to paint for the summer months.

Munch seemed to have the same restless and disturbed spirit as Van Gough. There are elements in his work - a pronounced wandering line - that was symptomatic of a restlessness which caused him to move about Germany and between Paris and Berlin for years, staying in boarding houses and often ending up hungry and exhausted.

In 1896 he returned to Paris where he spent the next two years and had some successful exhibitions. He met some friends in Paris but loneliness is a persistent theme in his work. Although he had affairs with a number of women, he never married. The family history of tuberculosis and mental illness convinced him that it was unwise to marry and besides, he feared that marriage would interfere with his work.

In 1908 the crisis of his health came to a head. A number of things contributed to his nervous breakdown - alcohol, overwork, emotional strain and criticism of his work in his native country. He suffered from hallucinations and felt he was going mad. He was determined to deal with his problems and entered a clinic in Copenhagen. After some months there he was pronounced cured.

From then on he lived near Oslo, mostly at Kragero, a small costal town facing an archipelago of wooded islands where he painted landscapes and self portraits. For the rest of his life he was to receive much recognition in his native country.

Like many other artists, including Van Gough, Munch was briefly influenced by Impressionism and neo-Impressionism and the pointillism of Seurat and Signac. From Impressionism he took their bright, pure colours, their casual, informal approach to the subject, and the new status of the sketch as a finished picture. He painted mostly from memory

Spring Day on Karl Johan Street. 1891. Edvard Munch. Billedgalleri, Bergen.

This painting - typical of Impressionism - of a sunny day in the main thoroughfare of Oslo looking towards the royal palace, is done in the pointillist style of multicoloured spots of paint, and applied in this case, rather loosely. Oslo is depicted as a place where you can enjoy yourself with your friends by going for a stroll in the afternoon sun. There is a carnival atmosphere. The place looks open and inviting – shades of Impressionist Paris.

Munch hardly ever again painted a picture like this. He rejected the anti-humanistic character of Impressionism, with its emphasis on patterns of coloured light in which people and objects were dissolved. He also felt temperamentally alienated from the sunny side of life typical of the Parisian middle classes.

Evening on Karl Johan Street. 1892, Rasmus Meyer Collection, Bergen

This painting, done a year later than the last one, depicts the same scene but without the bright sunny colours. In this picture, the city is a grim place where people are depersonalised, a place of lonely crowds and artificial distractions.

The life of the street changes from happiness to horror. On the pavement a mass of middle-class people with dehumanised, zombie-like faces glide mechanically towards us.

Their fashionable appearance and stylish dress belies their spiritual deprivation. Although they are close together, there is no communication between them. They are a lonely crowd, typical of the city. In the middle of the street, a solitary man, probably the artist himself, walks in the opposite direction, symbolising his isolated existence and his refusal to go along with the tide? In the distance in front of him is the Norwegian parliament building, symbol of authority, its windows like eyes, lit up threateningly with ghostly lights. Not only the buildings, everything in the picture has a threatening, oppressive appearance, including the towering tree on the right. Compare this with the friendly, homely buildings and trees of Spring Day where all the objects were keeping their distance so to speak. Here there is claustrophobia. The plunging perspective brings the objects in the picture closer to the viewer. Their size and dark tones bring them closer still. The crowd appears to be moving out of the bottom of the picture as if in an effort to escape the horror. The painting echoes Van Gough, in his view of nature as threatening and oppressive.

While Spring Day was probably painted from observation, Munch's approach henceforth was to represent scenes based on memory or imagination instead of immediate observation. This approach tended to simplify forms into flat patterns. Our mind's eye forgets details and sees things in the flat rather than the round. Instead of the Impressionist system of three-dimensional modelling in colour gradations, he adopted a style of flat areas of colour enclosed by lines. This is evident here in the large tree on the right, in the buildings and in the figures.

There is distortion of perspective, colour, tone and form for expressive purposes. His plunging perspective and dark, sombre tones evoke a sombre, claustrophobic mood, as if the stench of death hung over the place. His colour is subdued to suit the sombre themes of death and suffering.

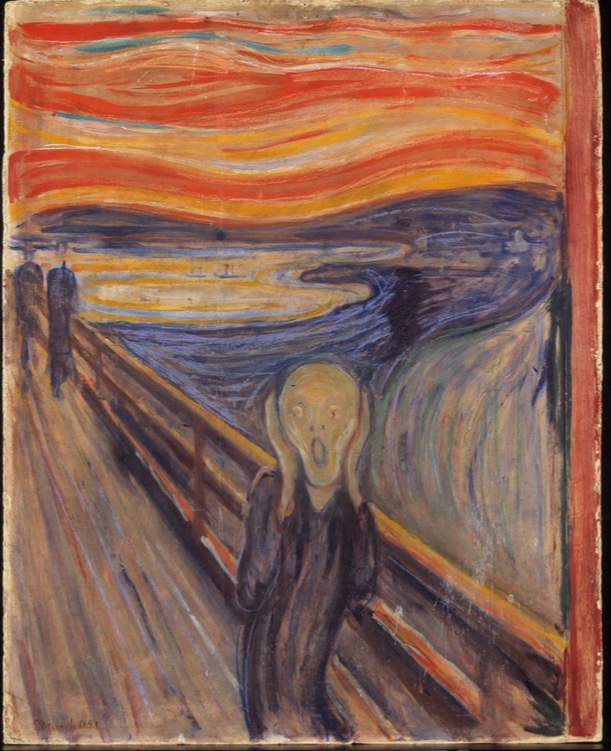

The Scream. Edvard Munch. National Museum of Art, Architecture and Design, Oslo.

As in a number of Munch's paintings of this period, the setting is Asgardstrand on the Oslo fjord with the same curving shoreline. 'One evening', wrote Munch, 'I was walking along a path, the city on one side, the fjord below. I felt tired and ill...The sun was setting and the clouds turning blood red. I sensed a scream passing through nature. It seemed to me that I heard the scream. I painted the clouds as actual blood. The colour shrieked.'

Here again, there is distortion of colour, line, form and perspective. The slow-flowing, horizontal lines in the sky soon widen into streams of colour and suddenly change direction into a mad rushing diagonal flow down towards the bottom of the picture. The plunging perspective of the roadway and the diagonal straight line of the railing indicate a more rapid flow from the opposite side of the painting. While this, in a sense, holds back the plunging curves and prevents the figure from being overwhelmed or crushed by nature, there still remains the need to escape from a bruising experience. Is Munch expressing his reaction to the memory of death in his family represented by the two shadowy figures in the distance, and is this a memory he finds unbearable? Can he ever escape from it?

This picture, like so much of Munch's work of this period, is essentially expressive. There is the clash of opposite colours - orange and blue. Do red and blue symbolise violence and death respectively? Does the memory of a violent and oppressive father still linger? There is more violence in the clashing line and distortion of the figure. Good for a creative response.

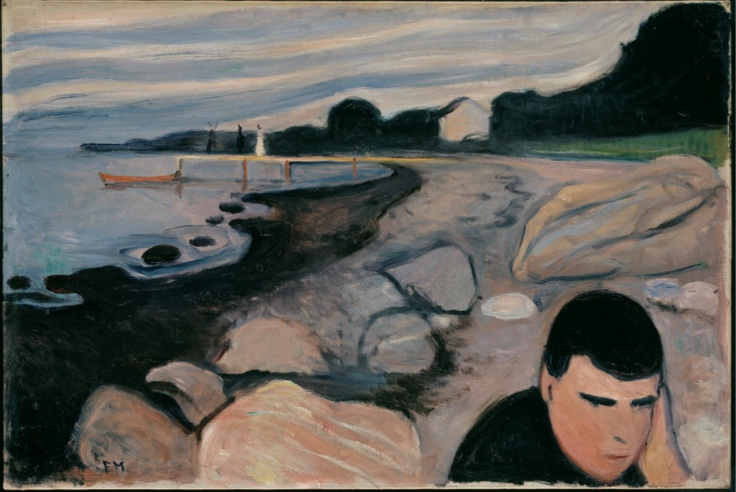

Melancholy, Edvard Munch. The National Museum of Art, Architecture and Design, Oslo.

Various versions exist of this composition. The image of the despondent male isolated in nature and sometimes separated from a woman, was frequently used by Munch in the 1890s.

A figure sits in deep contemplation among the rocks of Asgardstrand. In the distance the figures of a man and woman are about to embark on a boat, the undulating shoreline linking them to the foreground figure. The silhouetted line of trees looms threateningly.

In some of the figure paintings Munch uses profile views of foreground figures to denote states of contemplation, the object of such contemplation being shown in the background. His memory of the scene in the background gives us a clue concerning the thoughts and feelings of the man sitting on the rocks. Thus we can speculate regarding his feelings. Was it jealousy, loneliness, rejection, loss? The sombre late evening light also helps to define the melancholic mood of the painting.

The Virginia Creeper. 1900, Munch Museum, Oslo.

n some of Munch's paintings, frontal views can imply a sharp emotional and physical reaction to the memory image in the background when that image is closer to the foreground figure in space and time. In this painting, the house is so close as to be almost alling on top of the figure. What is this frightening vision from which the man is striving to escape? His truncated head at the base line suggests death. Everything in the picture seems to suggest death - the barren tree with the stump of a severed branch, the house strangled by a bloody parasite. The house suggests some menacing presence with its multiple eyes and central nose-like element. Is Munch, in fact, haunted by the memory of the house of his childhood?

Normally, a house has connotations of peace, love, harmony and general homeliness. Perhaps for Munch, a house was associated with pain, oppression and death. Here, the virginia creeper seems to be running down the walls in streams of blood, threatening to engulf the man with his red eyes and fearful greenish face. Note the clash of red and green,the symbolic use of strong, pure colours and the distortion of form. Compare this picture with one of Van Gough’s later works.

The Storm, 1893. Museum of Modern Art, New York.

The Scream, Melancholy and The Storm are among three of the many paintings with the setting of Asgardstrand. This picture is a reference to a storm witnessed there by a friend of the artist. Munch, however is more concerned with the psychological effects of the storm than mere reportage.

The shadowy wives of the fishermen are huddled together, with hands to their ears – echoing The Scream – as if attempting to shut out the terrors of nature. They have left the security of the house, with its lights, to confront the treacherous darkness. Was he thinking of Van Gough’s The Starry Night? The wind is indicated by the leaning tree and the scarf of the figure in white. What is the significance of the figure in white?

Compare this painting with The Starry Night. As a further follow up, children could respond in paint to their own experience of storms.

One possible follow up to a discussion on The Virginia Creeper would be a response in creative writing with perhaps a title – House of Horrors.

See also The Sick Child, 1886, National Gallery, Oslo. The picture records the fatal illness of Munch’s sister, Sophie The sorrowing woman is Sophie’s aunt, Karen. The joining of the hands – almost fused together - expresses the love between the two figures. In a sense, the sufferer and the one who grieves become one. In another sense the two are separated, each absorbed in her own emotions, or as if they are incapable of communicating with each other. The sick girl gazes yearningly across her aunt towards the window. We are shown nothing outside the window. The dark curtain intervenes, cutting off any idea of the world beyond. Perhaps there is no ‘beyond’.

Munch believed the picture marked a turning point in his art, that it ‘provided the inspiration for the majority of my later works.’